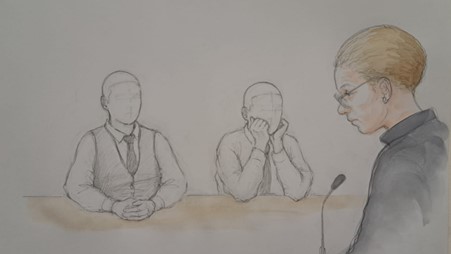

Last week saw two notable moments in the UK. One was the sentencing of two boys who were 12 years old when they murdered Shawn Seesahai with a machete in a park in a horrific attack, making them the youngest children sentenced to murder since the killers of James Bulger in 1993.

Upon reading the media reports, it became immediately obvious to me that the mention of domestic violence in their childhoods is significant. The first boy had grown up with violence at home, and the second boy had spent time in a refuge. Remember that this means that his family were put in emergency accommodation likely out of area because their risk of murder was assessed as significant.

So these boys have grown up with violence and then have found themselves committing such an act at such a young age. Now, my research has focused on the experiences of boys who live with domestic violence and then become involved in life ‘on-road’, street-life, in gangs, and often committing ‘serious youth violence’. When I was hearing stories from survivors and using the lens of masculinities, I found that the situation is much more complex than ‘learning violence from your father’ or ‘violence due to lacking male role models’.

Rather, my research looked at how boys cope with those early experiences of male violence, how they cope with their position as victims, and how they harness violence as a way to seek power, to reject victimhood, to enact frustrations, to express their anger and a whole host of feelings, which means I argue that we need to support boys in a gender-specific way around domestic violence.

But aligned to this last week, we also saw the Metropolitan Police announce that they are taking a ‘child first’ approach for the next five years. This is a welcome shift, because taking a child first approach is about seeing children as children, and not over-responsibilising them in the criminal justice system (building on the work by Haines and Case). A ‘child first’ approach is also essential because we know that most perpetrators of youth violence are also victims of violence. There is a huge grey area.

I noticed that domestic violence was part of this Met Police strategy. They note at the outset;

“The protection challenges they present for officers are wide-ranging: from a 13 year old being exploited and forced to transport drugs to an 8 year old growing up in a home full of domestic abuse, or a violent 17 year old with a knife.” (pg. 5)

This is welcome, but in my research, all of these examples would have been the same boy; domestic violence at home, exploited and dealing drugs, violent with a knife. But despite this the siloed mindset continues.

What was notable to me in the strategy was that there no gender-specific mentions of domestic violence being predominantly male perpetrated (instead they note, ‘25.8% of children live in a household where an adult has experienced domestic abuse’); Obscuring the significance of gender in DVA perpetration. Likewise, the word ‘boy/boys’ was not mentioned at all, nor was ‘masculinity’. And in fact, children who experienced domestic violence, it said, were dealt with under the ‘violence against women and girls strategy’. So not only was gender not mentioned, but it was only mentioned in relation to girls.

I would argue that this is a big mistake. By not framing domestic violence as predominantly male violence, and not naming youth violence as predominantly male violence, we therefore invisibilize the fact that girls and boys have gendered responses to domestic violence. Being a boy with a violent father means something different than experiencing this as a girl.

This gender-neutral strategy perpetuates a blind spot, which means that we are not going to be able to reach out to those boys, such as those who’ve just been sentenced to murder.

We need to be moving beyond a child first approach to an approach which supports ‘girls and boys’ according to their specific gendered needs and expressions. And this is not to stereotype, because we can talk about gendered ways of working without typecasting all boys as needing the same responses, but at the moment, without talking about masculinity, many of our interventions promote a specific expression of boyhood, for instance, the popularity of boxing programs for boys who are at risk of youth violence.

Now we need to open up a conversation around masculinities plural and how boys experience violence at home, we may be able to have more nuance around whether boys who’ve experienced violence want to go to boxing. Likewise, do child survivors of domestic violence who are unsupported need “Education and Engagement, e.g. sharing stories of those impacted by knife crime” as early as primary school? Is this trauma-informed? Is this tackling the root issue?

What if we are spending money on the wrong intervention at the wrong moment?

Actually, we should be supporting children with domestic violence support and funding that … but that is constantly overlooked. It is never hitting the headlines in the same way. We need to see child-focused support for domestic violence as an essential part of the ‘knife crime’/youth violence ecosystem.

We have the data and the research to support it. We just need those in power to listen.

Policy recommendations related to this topic can be read here